Written by: Jenna Kerry, MSc

Written by: Jenna Kerry, MSc

Published: February 26, 2025

Introduction

The Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) is a key player in the ability of the immune system to detect and respond to foreign invaders, such as viruses, bacteria, and even cancer cells. Made up of a set of genes known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes, MHC molecules are expressed on the surface of nearly every cell in the body. They function by presenting small peptide fragments from pathogenic proteins to T cells to trigger immune responses.

MHC molecules are categorized into two classes: Class I and Class II. MHC Class I molecules, found on almost all cells, present intracellular peptides to cytotoxic T cells. In contrast, MHC Class II molecules are primarily expressed on antigen presenting cells like dendritic cells and macrophages, presenting extracellular peptides to helper T cells to initiate a broader immune response.

At the forefront of immunotherapy research is exploitation and manipulation of the MHC and its downstream effector functions in an attempt to develop targeted therapies, particularly to treat cancer, autoimmune disease, and infectious diseases.

MHC Cancer Therapeutics

Cancer cells often develop mechanisms to evade immune detection, with one of the primary strategies being evasion of antigen presentation by MHC molecules. This enables tumors to hide from immune surveillance, making it harder for the body to elicit an immune response against the cancer cells. MHC therapies aim to counteract this immune evasion technique by enhancing the visibility of cancer cells to immune cells.

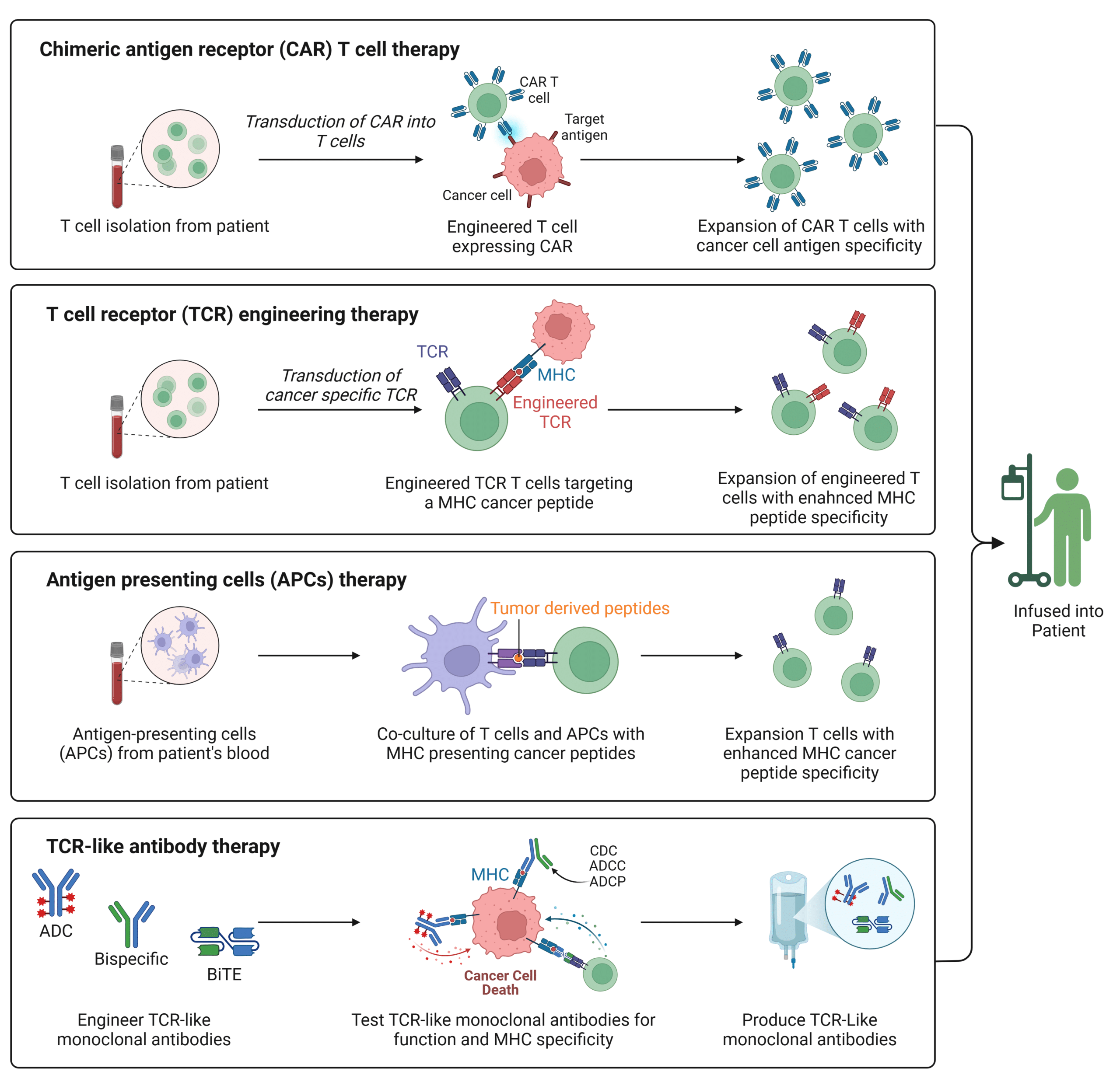

A variety of therapeutic approaches focus on manipulating MHC antigen presentation to strengthen the immune response against cancer cells. Drugs that influence the interaction between MHC molecules and T cells have been developed for a range of diseases. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapies aim to bypass the MHC pathway altogether (Figure 1). This approach involves genetically engineering a patient’s T cells to express a receptor that recognizes specific cancer associated antigens that are not presented by the MHC. While CAR-T therapy has shown success in treating hematologic cancers, such as FDA approved therapies like Kymriah and Yescarta, its effectiveness with solid tumors remains limited. This limitation is primarily due to the challenge of identifying specific surface biomarkers on tumor cells.

Given that most cancer specific antigens are intracellular, researchers are starting to focus on harnessing the MHC pathway, rather than bypassing it, to improve cancer therapeutics. A promising avenue involves enhancing T cell receptor (TCR) recognition of peptides presented by MHC molecules through genetic engineering (Figure 1). This process includes cloning TCRs specific to MHC peptides follow by transduction into normal T cells via retroviral vectors, thereby enabling them to recognize and target cancer cells. Currently, over 84 clinical trials are exploring TCR engineered T cell immunotherapies. Both CAR-T and TCR engineered T cell approaches are evolving toward multi- and co-antigen targeting to enhance both safety and efficacy. Additionally, antigen presenting cells (APCs) can be used in T cell therapy to enhance MHC peptide specific T cell response (Figure 1).

Recent advancements focus on TCR-like (TCRL) antibodies, which offer advantages over traditional TCRs for MHC targeting (Figure 1). These antibodies, designed to target cancer antigens presented by MHC molecules, can be used in formats like antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and bispecific T cell engagers (BiTEs), expanding the range of targeted antigens. With improved stability, affinity, and ease of production, TCRL antibodies overcome limitations of traditional TCRs and show promise for more effective treatments, including for solid tumors.

Figure 1: Summary of MHC Based Cancer Therapeutics.

MHC Autoimmune Disease Therapeutics

Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system mistakenly targets the body’s own cells, often due to failures in self tolerance mechanisms. Researchers are exploring ways to manipulate MHC interactions to suppress or redirect the immune response, preventing it from attacking healthy tissues. Strategies include designing therapeutics that either block the MHC presentation of self antigens to T cells or exploit the MHC to reprogram the immune system to tolerate self tissues.

MHC class II molecules play a critical role in presenting self antigens to T cells to maintain self tolerance. Specific MHC class II alleles are linked to the susceptibility or resistance to autoimmune diseases. For instance, inherited polymorphisms in HLA-II genes are frequently associated with autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease (CD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and type 1 diabetes. Targeting these MHC molecules with specific therapies aims to correct or modulate the immune response that leads to autoimmune diseases.

In autoimmune disorders like multiple sclerosis (MS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), therapies based on presenting self antigens or their mimics through MHC molecules are being developed to induce immune tolerance. For example, MHC nanomedicines have been shown to reprogram autoantigen specific T cells into regulatory T cells, which help suppress autoimmunity while preserving normal immune function. Additionally, therapies like glatiramer acetate, used to treat MS, bind to MHC molecules and block their interaction with self antigens, preventing the immune system from attacking the body’s own tissues.

TCRL monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) offer promising treatments for autoimmune diseases by targeting the MHC-autoantigen complexes to modulate immune responses. They can deplete pathogenic cells or reduce T cell activation through mechanisms such as blocking MHC autoantigen presentation. Bispecific antibodies, mAb drug conjugates, and mAb cytokine conjugates enhance targeted therapies, promoting immune tolerance. For example, bispecific antibodies with specificity for CD20+ B cells and autoantigen bound MHC complexes selectively deplete only the B cells associated with autoimmune pathology. Additionally, TCRL antibodies are being used in CAR-T cell therapies to selectively target and deplete autoantigen presenting cells, providing a new approach to treating autoimmune diseases. For example, CAR-T cells expressing a TCRL antibody targeting MHC bound to insulin peptide complexes have been shown to modulate autoimmunity in diabetic mice.

MHC Infectious Disease Therapeutics

MHC therapeutics are gaining significant attention in the fight against infectious diseases. The MHC plays a vital role in defending the body against infectious disease by facilitating the presentation of pathogen derived peptides to T cells, which triggers a targeted immune response.

Recent research has revealed that certain MHC II alleles are associated with susceptibility to infectious diseases like hepatitis B, dengue, and West Nile virus. Some viruses have even evolved mechanisms to evade the immune system by altering or reducing MHC II expression. For example, HIV impairs MHC II presentation by promoting the surface expression of immature MHC II molecules, making it harder for the immune system to elicit a defense.

MHC therapeutics are being increasingly explored, particularly in vaccine development. A deeper understanding of MHC antigen presentation is essential for designing vaccines that elicit more robust and long lasting immune responses, particularly against challenging pathogens like HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis.

For example, a recent study explored a promising SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, where the spike receptor binding domain was fused with a nanobody. This nanobody targets and binds to MHC class II molecules, stimulating a powerful immune response through helper T cells. The study demonstrated that the vaccine induced the production of neutralizing antibodies in mice, as well as a strong T cell mediated immune response.

MHC therapeutics are also expanding beyond vaccines. One promising example is the development of adoptive T cell therapies, which involve genetically modifying T cells to better recognize and eliminate infected cells. These therapies often rely on MHC molecules to help T cells identify infected cells, enhancing the effectiveness of the treatment. In some cases, MHC presentation can be bypassed altogether, as seen in clinical trials like the HIV-1 multi-antigen specific T cell therapy (NCT03485963), which has shown potential in managing HIV infections by targeting multiple HIV-1 antigens simultaneously.

MHC Therapeutics Computational Methods

The development of MHC therapeutics, like cancer immunotherapies and T cell therapies, depends on accurately predicting which peptides bind to specific MHC molecules. Traditional experimental methods are time consuming and costly, but computational approaches have revolutionized this process, making it faster and more precise.

Machine learning models like NetMHCpan and RPEMHC predict peptide to MHC binding by analyzing large datasets of known interactions. These models can predict binding across multiple MHC alleles, making them valuable for developing therapies for diverse populations. Deep learning methods, such as DeepMHCII, offer even more accuracy by identifying complex patterns in the data. The use of databases, such as the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB), also helps refine these predictions by providing extensive data on known peptides to MHC interactions.

The main advantage of using computational predictions is the speed at which researchers can identify promising peptide candidates for therapeutic development. These tools allow for rapid screening of large peptide libraries, accelerating the design of targeted vaccines, mAbs, and T cell therapies. Computational methods also help personalize treatments by predicting peptides specific to an individual’s MHC alleles, ensuring better efficacy and reduced risk of adverse effects.

Despite these advancements, challenges still remain, including predicting peptides with rare sequences and understanding the full complexity of immune responses. For example, the accuracy of computational methods for MHC cancer antigen prediction falls below 50%. Factors such as non-cancerous peptide similarity and immune tolerance mechanisms can prevent T cells from recognizing certain cancer antigens. As a result, computational predictions are valuable for guiding experimental efforts, but only through rigorous peptide binding assays and immunological testing can the actual efficacy of these predictions be validated. However, as AI continues to improve and more data becomes available, the accuracy and versatility of these models will keep improving.

Immunopeptidomics

Immunopeptidomics focuses on identifying the peptides that bind to MHC molecules (Figure 2). By analyzing the peptides presented on MHC molecules, researchers gain a deeper understanding of how the immune system can be harnessed for targeted disease therapeutics. Immunopeptidomics provides important insights into MHC presented peptide characteristics, MHC binding motifs, and factors influencing peptide generation and presentation.

Currently, mass spectrometry (MS) immunopeptidomics is the gold standard for analyzing peptides presented on MHC molecules. By using immunoaffinity purification, scientists can extract peptides from various biological samples, such as tissues, tumors, and body fluids, enabling the identification of antigens that trigger an immune response. This information is key for developing targeted therapeutics, including personalized cancer immunotherapies, vaccines, and treatments for autoimmune disorders.

For example, immunopeptidomics analysis led to the creation of cancer vaccines, such as the IMA901 vaccine for renal cell carcinoma (RCC). This multi-peptide vaccine, formulated using tumor antigens identified by MS, showed promising results in early trials. Although phase 3 trials didn’t show extended survival compared to the standard treatment, the approach proved feasible for cancers like prostate cancer and glioblastoma.

Immunopeptidomics was also used in a 2019 study by Hilf et al., where peptide selection was applied to create personalized vaccines for glioblastoma patients. The study showed that the APVAC1 vaccine, based on top ranked peptides, triggered positive immune responses. A similar strategy has been used for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients, with personalized multi-peptide vaccine (CLL-VAC-XS15) which was tailored to each patient’s HLA profile and immunopeptidome analysis. This clinical trial concluded that the vaccine induced strong and long lasting T cells while also demonstrating safety and tolerability.

The potential of immunopeptidomics extends beyond cancer vaccines, enabling the development of novel therapies like TCR enhancers, CAR-T cells, and antibodies targeting MHC peptide complexes to treat a variety of diseases. In fact, a study employed immunopeptidomics to identify a unique cancer related antigen (COL6A3) and use it to enhance T cells to target and destroy cancer cells.

Current efforts are focused on combining immunopeptidomic LC-MS/MS datasets to help computational methods determine binding motifs and study the rules of peptide processing and presentation. Many prediction methods now use LC-MS/MS data, such as MARIA, MixMHC2pred, and neonmhc2, which integrate MHC peptide datasets for more accurate predictions.

Figure 2: Overview of Immunopeptidomics Workflow.

Accelerating Immunopeptidomics with Rapid Novor’s AI Algorithm

Rapid Novor’s Novor AI algorithm has revolutionized immunopeptidomics by enabling fast, de novo sequencing and analysis of MHC bound peptides. This approach enhances immunopeptidomics studies, offering clearer insights into immune responses to pathogens, cancer, and therapies.

De novo sequencing allows identification of novel peptides, speeding up the discovery of potential vaccine and immunotherapy targets.

In 2023, Rapid Novor and Bruker launched PaSER™ Novor – specifically tuned to Bruker instruments such as TIMS-TOF – and demonstrated improved speed and accuracy, making peptide sequencing more efficient and precise. PaSER Novor is available for license directly through Bruker.

If you want to license Novor AI for use with other mass spectrometers, or if you’d like Rapid Novor to perform de novo sequencing, contact our scientists for more information.

Talk to Our Scientists.

We Have Sequenced 10,000+ Antibodies and We Are Eager to Help You.

Through next generation protein sequencing, Rapid Novor enables reliable discovery and development of novel reagents, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Thanks to our Next Generation Protein Sequencing and antibody discovery services, researchers have furthered thousands of projects, patented antibody therapeutics, and developed the first recombinant polyclonal antibody diagnostics.

Talk to Our Scientists.

We Have Sequenced 9000+ Antibodies and We Are Eager to Help You.

Through next generation protein sequencing, Rapid Novor enables timely and reliable discovery and development of novel reagents, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Thanks to our Next Generation Protein Sequencing and antibody discovery services, researchers have furthered thousands of projects, patented antibody therapeutics, and ran the first recombinant polyclonal antibody diagnostics